Brother Mark Twain’s ‘A Letter from Santa’

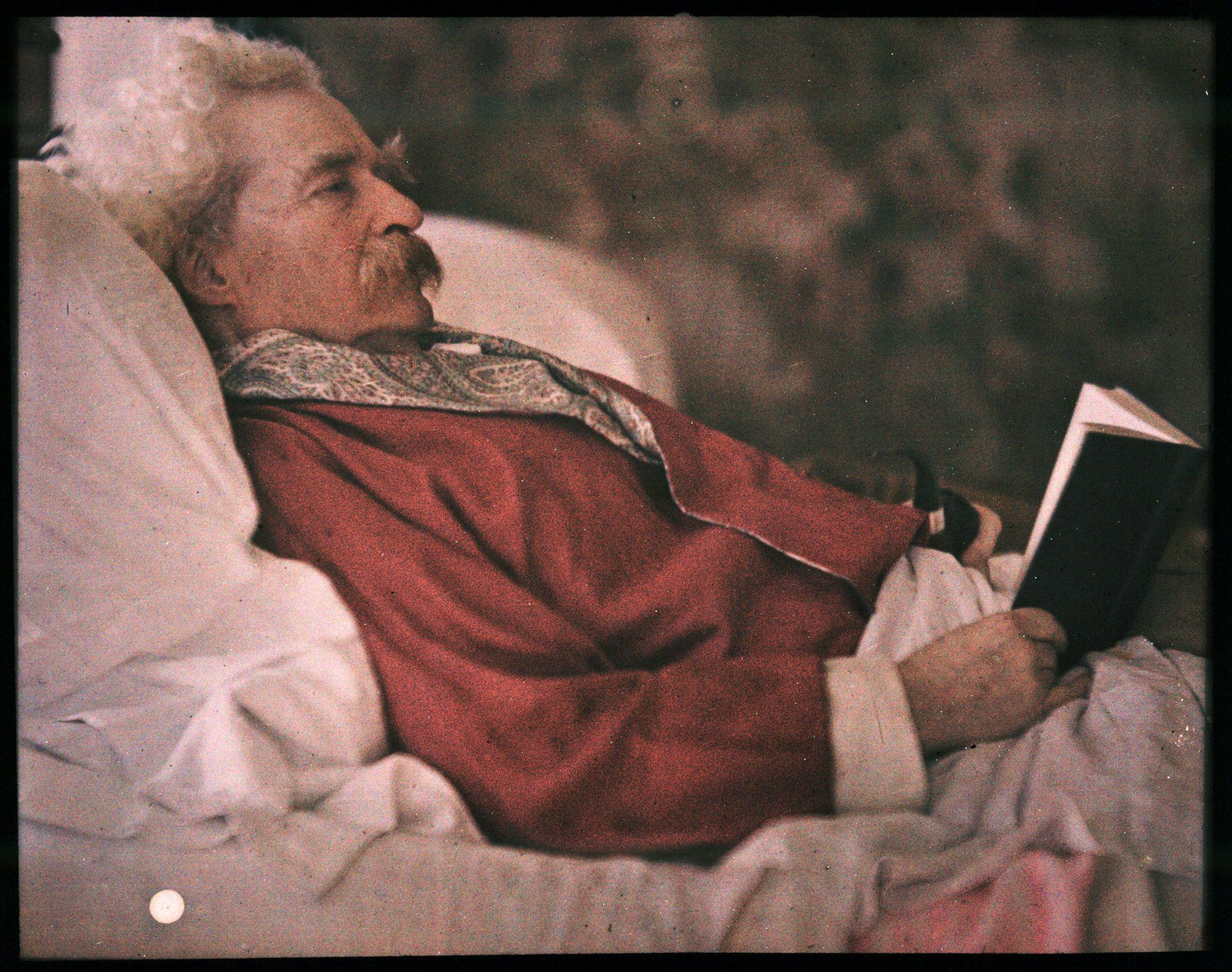

Samual Langhorne Clemens, more popularly known by his pen name, Mark Twain, is one of the great American writers. He was so influential in his day that he is often considered the "Father of American Literature." Born on November 30th, 1835, in Florida, Missouri, Twain led many lives, including spending time as a riverboat pilot and world traveler. Twain was also a Freemason initiated as an Entered Apprentice at Polar Star Lodge on February 18th, 1861.

As an author, Brother Twain published over 20 novels and dozens of short stories, essays, and lectures, including his most famous work, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which mixed satire with thought-provoking prose. Yet, amid the pages of his illustrious repertoire, a lesser-known gem adds a touch of festive merriment to Twain's legacy: "A Letter from Santa Claus." As the holiday season approaches, it is only fitting to delve into the whimsical realm crafted by Brother Twain in this heartwarming missive from the North Pole.

A Christmas Story

In 1875, Brother Twain wrote a letter from the perspective of Santa Claus for his three-year-old daughter, Susie. The note, which he placed on her pillow Christmas morning, offers a unique blend of satire, wit, and a dash of Yuletide charm. Through the eyes of the celebrated American author, we discover a Christmas tale that goes beyond the customary festivities, inviting readers to revel in the author's playful spirit and find joy in this literary holiday treasure.

The letter highlights the compelling bond Brother Twain had with his daughter Susie. Born Olivia Susan Clemens, she was his second child and eldest daughter. She was the inspiration for a number of her father's works and had an affinity for the written word herself. When she was just 13, she wrote a biography about him, which Brother Twain later published in his autobiography. Of her writing, he wrote, "I had had compliments before, but none that touched me like this; none that could approach it for value in my eyes."

Susie followed her father into the world of arts and literature, attending Bryn Mawr College in 1890, where she starred as Phyllis in the play Iolanthe. During and after college, her young career was a series of peaks and valleys. She traveled abroad with her family, attempted to become an opera singer, and struggled to live in the long shadow of her father's fame. She tragically passed away on August 18, 1896, when she was just 24. She had developed a fever that turned into spinal meningitis while visiting her home in Hartford, Connecticut. Her father was heartbroken by the loss of his beloved daughter. Susie's complete biography of her father, Papa: An Intimate Biography of Mark Twain, was published in 1988.

Mark Twain, Father and Freemason

After he joined Polar Star Lodge No. 79 in St. Louis, Missouri, Brother Twain was raised to the Sublime Degree of Master Mason. However, he soon departed for the Nevada Territory to join his brother Orion on his adventures in the West. Naturally, his absence from the lodge resulted in a short-term suspension of his membership. However, there is evidence that Brother Twain visited Masonic lodges throughout the western United States during his travels. He was soon reinstated to the Polar Star Lodge when he returned from the Nevada Territory.

As Brother Twain reached the height of his fame near the end of the 19th century, he embarked on a world lecture tour. He visited Australia, India, Canada, and many countries throughout Europe. He soon realized there were Masonic connections to be found no matter where he was. He was famously intrigued by Lebanon's connection to the Craft, gifting a hand-crafted gavel to the Worshipful Master back at Polar Star Lodge.

Of course, the extent to which Freemasonry directly impacted Brother Twain’s literary works is a matter of interpretation. He had a complex and multifaceted personality shaped by the intellectual currents of his time and his extensive travels. What we do know is that his A Letter from Santa Claus is a literary holiday treasure.

The complete letter, which is to Susie as if from Santa Clause himself, follows here:

MY DEAR SUSIE CLEMENS:

I have received and read all the letters which you and your little sister have written me by the hand of your mother and your nurses; I have also read those which you little people have written me with your own hands—for although you did not use any characters that are in grown people’s alphabet, you used the characters that all children in all lands on earth and in the twinkling stars use; and as all my subjects in the moon are children and use no characters but that, you will easily understand that I can read your and your baby sister’s jagged and fantastic marks without trouble at all. But I had trouble with those letters which you dictated through your mother and the nurses, for I am a foreigner and cannot read English writing well.

You will find that I made no mistakes about the things which you and the baby ordered in your own letters—I went down your chimney at midnight when you were asleep and delivered them all myself—and kissed both of you, too, because you are good children, well-trained, nice-mannered, and about the most obedient little people I ever saw. But in the letter which you dictated, there are some words that I could not make out for certain, and one or two small orders which I could not fill because we ran out of stock. Our last lot of kitchen furniture for dolls has just gone to a poor little child in the North Star away up in the cold country about the Big Dipper. Your mama can show you that star and you will say: “Little Snow Flake” (for that is the child’s name) “I’m glad you got that furniture, for you need it more than I.” That is, you must write that, with your own hand, and Snow Flake will write you an answer. If you only spoke it she wouldn’t hear you. Make your letter light and thin, for the distance is great and the postage heavy.

There was a word or two in your mama’s letter which I couldn’t be certain of. I took it to be “a trunk full of doll’s clothes.” Is that it? I will call at your kitchen door at just about nine o’clock this morning to inquire. But I must not see anybody, and I must not speak to anybody but you. When the kitchen doorbell rings George must be blindfolded and sent to open the door. Then he must go back to the dining room or the china closet and take the cook with him. You must tell George that he must walk on tiptoe and not speak—otherwise, he will die someday. Then you must go up to the nursery and stand on a chair or the nurse’s bed and put your ear to the speaking tube that leads down to the kitchen and when I whistle through it you must speak in the tube and say, “Welcome, Santa Claus!” Then I will ask whether it was a trunk you ordered or not. If you say it was, I shall ask you what color you want the trunk to be. Your mama will help you to name a nice color and then you must tell me about every single thing in detail which you may want the trunk to contain. Then when I say “Goodbye and a Merry Christmas to my little Susie Clemens,” you must say “Good-bye, good old Santa Claus, I thank you very much and please tell Snow Flake I will look at her star tonight and she must look down here—I will be right in the West bay-window; and every fine night I will look at her star and say, ‘I know somebody up there and like her, too.’” Then you must go down into the library and make George close all the doors that open into the main hall, and everybody must keep still for a little while. I will go to the moon and get those things and in a few minutes I will come down the chimney that belongs to the fireplace that is in the hall—if it is a trunk you want—because I couldn’t get such a thing as a trunk down the nursery chimney, you know.

People may talk if they want until they hear my footsteps in the hall. Then you tell them to keep quiet a little while till I go back up the chimney. Maybe you will not hear my footsteps at all—so you may go now and then and peep through the dining-room doors, and by and by you will see that thing which you want, right under the piano in the drawing room—for I shall put it there. If I should leave any snow in the hall, you must tell George to sweep it into the fireplace, for I haven’t time to do such things. George must not use a broom, but a rag—else he will die someday. You must watch George and not let him run into danger. If my boot should leave a stain on the marble, George must not holystone it away. Leave it there always in memory of my visit; and whenever you look at it or show it to anybody you must let it remind you to be a good little girl. Whenever you are naughty and somebody points to that mark which your good old Santa Claus’s boot made on the marble, what will you say, little Sweetheart?

Goodbye for a few minutes, till I come down to the world and ring the kitchen doorbell.

- Your loving SANTA CLAUS Whom people sometimes call the Man in the Moon.